The University of Edinburgh is participating in this year’s Festival of Museums, a Scotland-wide series of special exhibitions and activities that will take place the weekend of May 15th – 17th, with a romp through their most deadly collections. One Last Fright will include events like a talk about gruesome Victorian medical procedures as seen in prints collected by surgeon Sir John William Thomson-Walker, poisonous cosmetics and dyes from the University’s geology collection and A Scandal in Surgeons’ Hall, an evening of dancing, magic, fortune-telling and a recreation of a Victorian crime scene.

The University of Edinburgh is participating in this year’s Festival of Museums, a Scotland-wide series of special exhibitions and activities that will take place the weekend of May 15th – 17th, with a romp through their most deadly collections. One Last Fright will include events like a talk about gruesome Victorian medical procedures as seen in prints collected by surgeon Sir John William Thomson-Walker, poisonous cosmetics and dyes from the University’s geology collection and A Scandal in Surgeons’ Hall, an evening of dancing, magic, fortune-telling and a recreation of a Victorian crime scene.

The most popular event — tickets are already sold out but you can still add yourself to the waiting list — is a tour through the University’s collection of Arthur Conan Doyle books and related materials and best of all, a rare glimpse at a scrapbook relating to the Burke and Hare murders. The scrapbook, thought to have been compiled by a medical student shortly after the grisly events were exposed, has never been display in public before. Neither has its most gruesome page: a letter written in William Burke’s blood.

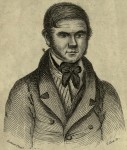

William Burke and William Hare were Irish immigrants who moved to Edinburgh looking for work as navvies (canal diggers). Burke arrived in Scotland around 1817 and worked the Union Canal. Hare arrived around that time or a little later and also worked the Union Canal. In 1826, he married a widow who owned a cheap but not entirely disreputable (meaning it wasn’t a brothel) flop house. Burke and Hare didn’t know each other or meet until 1827 when Burke and his common-law wife Helen McDougal moved into the same neighborhood as the boarding house. They became friends and, when opportunity struck, partners in murder.

William Burke and William Hare were Irish immigrants who moved to Edinburgh looking for work as navvies (canal diggers). Burke arrived in Scotland around 1817 and worked the Union Canal. Hare arrived around that time or a little later and also worked the Union Canal. In 1826, he married a widow who owned a cheap but not entirely disreputable (meaning it wasn’t a brothel) flop house. Burke and Hare didn’t know each other or meet until 1827 when Burke and his common-law wife Helen McDougal moved into the same neighborhood as the boarding house. They became friends and, when opportunity struck, partners in murder.

The late 18th and early 19th century saw an explosion of interest in medical studies. The University of Edinburgh was widely reputed to have the best medical school in Britain, if not Europe. So many students clamored to attend its lectures that private anatomy classes sprang up to service the demand. Dr. Robert Knox, a surgeon with a stellar reputation garnered attending to the wounded of the Battle of Waterloo, ran hugely popular anatomy, physiology and surgery courses starting in 1825. At their peak, his classes were attended by 400 students, more than attended all the other private anatomy lectures combined.

Knox’s advertisements emphasized that the every lecture would “comprise a full Demonstration on fresh Anatomical Subjects,” a very tall order when you consider that his 1828-9 Practical Anatomy and Operative Surgery lecture course ran from October 6th 1828 through the end of July 1829 with twice daily demonstrations, ie, dissections of human cadavers. “Arrangements have been made,” the ad assured prospective students, “to secure as usual an ample supply of Anatomical Subjects.”

Knox’s advertisements emphasized that the every lecture would “comprise a full Demonstration on fresh Anatomical Subjects,” a very tall order when you consider that his 1828-9 Practical Anatomy and Operative Surgery lecture course ran from October 6th 1828 through the end of July 1829 with twice daily demonstrations, ie, dissections of human cadavers. “Arrangements have been made,” the ad assured prospective students, “to secure as usual an ample supply of Anatomical Subjects.”

Just what those arrangements were turned out to be the sticking point. By law, only executed murderers who had been condemned to posthumous dissection were released to anatomy schools. There were nowhere near enough people hanging from the gallows to satisfy the voracious appetite of the University and the private lecturers. For Knox’s Practical Anatomy course alone, we’re talking 10 months of twice daily dissections. Even if he reused bodies a few times — let’s go so far as to say the same cadaver could last a week (highly unlikely) — he still would have needed more than 40 bodies just to get through that one course. Then there was his Physiology course to supply, plus the University’s and the lectures by all the other anatomists.

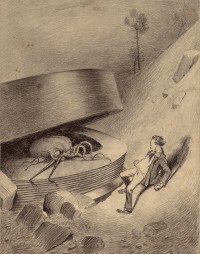

Where there’s demand, someone is going to come up with the supply, and those someones were known as body-snatchers, grave-robbers, ghouls or resurrection men. Digging up recently deceased bodies was highly lucrative work. Resurrectionists would be paid the equivalent of months of wages for a single body. It was the kind of work best performed by locals who knew who was dead or dying and who had relationships with bribable cemetery sextons and with the anatomists. Locals also knew their way around, necessary for surreptitious nighttime excavation and transportation of dead bodies, and could better avoid or pay off law enforcement.

Burke and Hare were not local. They had none of the connections and knowledge resurrection men needed to make their macabre living. In fact, they quite fell into selling bodies by accident. When an elderly lodger at the Hare boarding house named Donald died still owing £4 rent, Hare and Burke stole the body out of the coffin, replaced it with tanner’s bark, and then schlepped it to the University of Edinburgh where they had heard Professor Alexander Monro III, Chair of Anatomy, was always keen to take a dead body off a guy’s hands. They asked a student in the courtyard if any of Monro’s staff was about and the student suggested they take their merchandise to Robert Knox at Number 10 Surgeon’s Square instead.

Burke and Hare were not local. They had none of the connections and knowledge resurrection men needed to make their macabre living. In fact, they quite fell into selling bodies by accident. When an elderly lodger at the Hare boarding house named Donald died still owing £4 rent, Hare and Burke stole the body out of the coffin, replaced it with tanner’s bark, and then schlepped it to the University of Edinburgh where they had heard Professor Alexander Monro III, Chair of Anatomy, was always keen to take a dead body off a guy’s hands. They asked a student in the courtyard if any of Monro’s staff was about and the student suggested they take their merchandise to Robert Knox at Number 10 Surgeon’s Square instead.

There they found three of Knox’s assistants — Jones, Miller and Ferguson — and arranged to deliver Donald’s body after nightfall. Dr. Knox examined the corpse and determined its market value was £7.10s (more than $1,000 in today’s money). None of them asked any questions. They just told Burke and Hare that they would be glad to see them again when they had another body to dispose of. That was December of 1827.

A few months later they had another body to dispose of, only this time it was no accident. Hare got a lodger so drunk he (it might have been a woman; the order of murders is unclear) couldn’t move, then covered his mouth and nose while Burke laid his weight across his chest until he was smothered to death. They put the corpse in a chest and alerted Knox’s assistants that they had fresh material. Miller arranged for a porter to meet them for their convenience and the body was brought to Knox’s lecture rooms. Knox expressed approval at its fresh condition and gave them £10 for the body.

A few months later they had another body to dispose of, only this time it was no accident. Hare got a lodger so drunk he (it might have been a woman; the order of murders is unclear) couldn’t move, then covered his mouth and nose while Burke laid his weight across his chest until he was smothered to death. They put the corpse in a chest and alerted Knox’s assistants that they had fresh material. Miller arranged for a porter to meet them for their convenience and the body was brought to Knox’s lecture rooms. Knox expressed approval at its fresh condition and gave them £10 for the body.

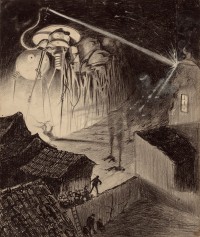

Thus began a pattern that would continue undisturbed for another year. Lodgers would come in and if they weren’t already ill, Mr. and/or Mrs. Hare would get them pass-out drunk so Burke and Hare could suffocate them without the victims being able to put up much of a fight. This method ensured there were no obvious marks on the body indicating murder so Knox and his crew could continue to ask no questions.

Burke and Hare killed at least 16 people before they were finally found out. The last victim was Mrs. Mary Docherty. They were extra sloppy this time, stashing her dead body under a bed that a lodger had left her stockings on. The lodger saw the body and went to the police. Instead of disposing of her promptly in the river or somewhere, they quickly brought the body to Knox and made yet another sale even though they knew the cops would be sniffing around. An anonymous tipster told the police to check Knox’s anatomy lecture rooms and there they found Mrs. Docherty.

Burke and Hare killed at least 16 people before they were finally found out. The last victim was Mrs. Mary Docherty. They were extra sloppy this time, stashing her dead body under a bed that a lodger had left her stockings on. The lodger saw the body and went to the police. Instead of disposing of her promptly in the river or somewhere, they quickly brought the body to Knox and made yet another sale even though they knew the cops would be sniffing around. An anonymous tipster told the police to check Knox’s anatomy lecture rooms and there they found Mrs. Docherty.

Burke, McDougal, Hare and Mrs. Hare were arrested. They had circumstantial evidence of two other murders — a young man names James Wilson (aka Daft Jamie) who was well known in the neighborhood and a beautiful young woman named Mary Paterson who was falsely rumored to be a prostitute — but charged them with Mrs. Docherty’s first because she was the only whose body had been found. The evidence was weak even in the one case because there was no proof she’d been murdered. Concerned Burke and Hare would get off by blaming each other, Lord Advocate Sir William Rae granted the Hares immunity if they testified against Burke.

Burke, McDougal, Hare and Mrs. Hare were arrested. They had circumstantial evidence of two other murders — a young man names James Wilson (aka Daft Jamie) who was well known in the neighborhood and a beautiful young woman named Mary Paterson who was falsely rumored to be a prostitute — but charged them with Mrs. Docherty’s first because she was the only whose body had been found. The evidence was weak even in the one case because there was no proof she’d been murdered. Concerned Burke and Hare would get off by blaming each other, Lord Advocate Sir William Rae granted the Hares immunity if they testified against Burke.

It was at the trial in December of 1828 that the notion that Burke and Hare had been resurrectionists came into play. The only reason there was any question of whether they were resurrection men was because Helen McDougal needed plausible deniability. She knew Burke and Hare were dealing in corpses, but if she could claim that she thought they had bought the bodies or robbed graves to get them, then she wouldn’t be an accessory to murder. It worked; the jury found the charge against her not proven. Burke was found guilty of the murder of Mrs. Docherty and sentenced to death and dissection.

It was at the trial in December of 1828 that the notion that Burke and Hare had been resurrectionists came into play. The only reason there was any question of whether they were resurrection men was because Helen McDougal needed plausible deniability. She knew Burke and Hare were dealing in corpses, but if she could claim that she thought they had bought the bodies or robbed graves to get them, then she wouldn’t be an accessory to murder. It worked; the jury found the charge against her not proven. Burke was found guilty of the murder of Mrs. Docherty and sentenced to death and dissection.

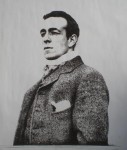

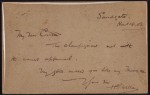

On Wednesday, January 28th, 1829, Burke was hanged. His body was delivered to the Edinburgh Medical College for dissection by Alexander Monro who immortalized the event by writing the following letter with the murderer’s blood.

On Wednesday, January 28th, 1829, Burke was hanged. His body was delivered to the Edinburgh Medical College for dissection by Alexander Monro who immortalized the event by writing the following letter with the murderer’s blood.

This is written with the blood of Wm Burke, who was hanged at Edinburgh on 28th Jan. 1829 for the Murder of Mrs. Campbell or Docherty. The blood was taken from his head on the 1st of Feb. 1829.

As was the custom at the time, Burke’s skin was used to bind books and make accessories, some of which are on display today at the University’s Anatomical Museum. Burke’s skeleton was preserved for anatomical study, as recommended by the Lord Justice-Clerk, David Boyle at sentencing: “I trust, that if it is ever customary to preserve skeletons, yours will be preserved, in order that posterity may keep in remembrance of your atrocious crimes.”

As was the custom at the time, Burke’s skin was used to bind books and make accessories, some of which are on display today at the University’s Anatomical Museum. Burke’s skeleton was preserved for anatomical study, as recommended by the Lord Justice-Clerk, David Boyle at sentencing: “I trust, that if it is ever customary to preserve skeletons, yours will be preserved, in order that posterity may keep in remembrance of your atrocious crimes.”

Monro’s letter made its way into the scrapbook along with news stories, songs and other references to the murders, trial and execution. It will be on display along with a petition signed by medical students around the time of the murders demanding more bodies be made available for anatomical studies. Ultimately the Burke and Hare murders solved the cadaver bottleneck once and for all. In 1832 Parliament passed the Anatomy Act allowing any unclaimed bodies to be given to medical schools for dissection before burial. That gave medical schools access to the great masses of dead paupers instead of the much thinner supply of murderers and put a virtually immediate end to the resurrection trade in the United Kingdom.

Monro’s letter made its way into the scrapbook along with news stories, songs and other references to the murders, trial and execution. It will be on display along with a petition signed by medical students around the time of the murders demanding more bodies be made available for anatomical studies. Ultimately the Burke and Hare murders solved the cadaver bottleneck once and for all. In 1832 Parliament passed the Anatomy Act allowing any unclaimed bodies to be given to medical schools for dissection before burial. That gave medical schools access to the great masses of dead paupers instead of the much thinner supply of murderers and put a virtually immediate end to the resurrection trade in the United Kingdom.

(In the US it went on for much, much longer, but that is another story and will be told another time.)

Trajan’s conquest of Dacia, so beautifully immortalized on the column that bears his name, was as immense a construction project as it was a military one. Trajan (r. 98-117 A.D.) built several major roads during his campaigns in Dacia, feats of engineering urged by the military necessity to clear a path for the organized and speedy movement of troops and supplies. The Via Trajana almost bisects central Bulgaria. It started in the Danube city of Ulpia Oescus, today the town of Gigen just south of the Romanian border, then went south through Sostra (modern-day Troyan) and the Troyan Pass in the Balkan Mountains before ending in Philippopolis (modern-day Plovdiv) which in Trajan’s day was in the Roman province of Thrace and is now in southern Bulgaria. The road played an important strategic role in the conquest of Dacia since it provided the army with a vital link connecting the Roman province of Lower Moesia on the Danube Plain with the largest city in Thrace. An even longer road Trajan built, the Via Militaris, intersected Philippopolis going the other way, diagonally from the northwest to the southeast of what is now Bulgaria.

Trajan’s conquest of Dacia, so beautifully immortalized on the column that bears his name, was as immense a construction project as it was a military one. Trajan (r. 98-117 A.D.) built several major roads during his campaigns in Dacia, feats of engineering urged by the military necessity to clear a path for the organized and speedy movement of troops and supplies. The Via Trajana almost bisects central Bulgaria. It started in the Danube city of Ulpia Oescus, today the town of Gigen just south of the Romanian border, then went south through Sostra (modern-day Troyan) and the Troyan Pass in the Balkan Mountains before ending in Philippopolis (modern-day Plovdiv) which in Trajan’s day was in the Roman province of Thrace and is now in southern Bulgaria. The road played an important strategic role in the conquest of Dacia since it provided the army with a vital link connecting the Roman province of Lower Moesia on the Danube Plain with the largest city in Thrace. An even longer road Trajan built, the Via Militaris, intersected Philippopolis going the other way, diagonally from the northwest to the southeast of what is now Bulgaria.  More recently, a team led by archaeologist Ivan Hristov have been excavating Sostra and environs since 2002. They found a stretch of the Via Trajana in 2010 that’s an impressive 7 meters (23 feet) wide and in excellent condition, the best preserved Roman road ever discovered in Bulgaria. Last year Hristov’s team unearthed a Roman road station 5,400 square feet in area with well-appointed facilities including a praetorium — a general or governor’s council/judgment hall — and baths with hot and cold water pools. The baths were fed by brick channels built to carry water from the Osam through the underfloor hypocaust system that heated the water, floor and walls. Coins, jewelry and votive offerings found at the bottom of one of the channels underscores that the people who made use of the facilities were wealthy. This wasn’t a modest public bath for the villagers; it was more like a luxury resort for the well-moneyed traveler.

More recently, a team led by archaeologist Ivan Hristov have been excavating Sostra and environs since 2002. They found a stretch of the Via Trajana in 2010 that’s an impressive 7 meters (23 feet) wide and in excellent condition, the best preserved Roman road ever discovered in Bulgaria. Last year Hristov’s team unearthed a Roman road station 5,400 square feet in area with well-appointed facilities including a praetorium — a general or governor’s council/judgment hall — and baths with hot and cold water pools. The baths were fed by brick channels built to carry water from the Osam through the underfloor hypocaust system that heated the water, floor and walls. Coins, jewelry and votive offerings found at the bottom of one of the channels underscores that the people who made use of the facilities were wealthy. This wasn’t a modest public bath for the villagers; it was more like a luxury resort for the well-moneyed traveler.  This year’s excavation has found a furnace used to heat up the water in a shallow pool next to the large swimming pool, much like the small hot tubs attached to the big pools in modern-day resorts. Hristov believes the resort regularly hosted government administrators and may even have been visited by the imperial family when they were in the area.

This year’s excavation has found a furnace used to heat up the water in a shallow pool next to the large swimming pool, much like the small hot tubs attached to the big pools in modern-day resorts. Hristov believes the resort regularly hosted government administrators and may even have been visited by the imperial family when they were in the area.